Naeem Mohaiemen is a writer and visual artist, working in Dhaka and New York. His essays, films, and photography explore the theme of failed utopias. Since 2006, he has been working on a long-form research project on the collapse of the ultra-left of the 1970s and the dangerous seduction of movements that promise revolution through violent confrontation. Mohaimen is a 2014 Guggenheim Fellow.

Ahmad Ghossein is an artist and filmmaker whose work draws on political history through personal narrative. He obtained his MA in visual art from the National Academy of Art, Oslo. Ghossein’s works include What Does Not Resemble Me Looks Exactly Like Me (2009); Faces Applauding Alone (2008); and 210m (produced by Ashkal Alwan, 2007); Yesterday’s News, a solo exhibition at Kunstforening Olso (2012); Relocating the Past, Ruins for the Future, a public space project (2013); and The Fourth Stage commissioned by the Sharjah Art Foundation (2015). His work has been shown at the Museum of Modern Art, New York; Berlin International Film Festival; International Short Film Festival Oberhausen; the New Museum, New York; Kunsthall Oslo; Home Works, Beirut; and Nikolaj Kunsthal, Copenhagen.

Since 2006, Mohaiemen has worked on a history of the 1970s revolutionary left, with Bangladesh as a focal point making linkages to parallel movements elsewhere. The research looks at forms of insurrectionary belonging as manifestations of a doomed masculinity project.

Part 1 centers on the 1977 hijack of JAL 472, a Hollywood actress on honeymoon, and an interrupted episode of The Zoo Gang. Unfolding in darkness, the film carries forward Naeem's long-term interest in text as a central visual object.

Part 3 of the project (Last Man in Dhaka Central) is currently on view at the 2015 Venice Biennale.

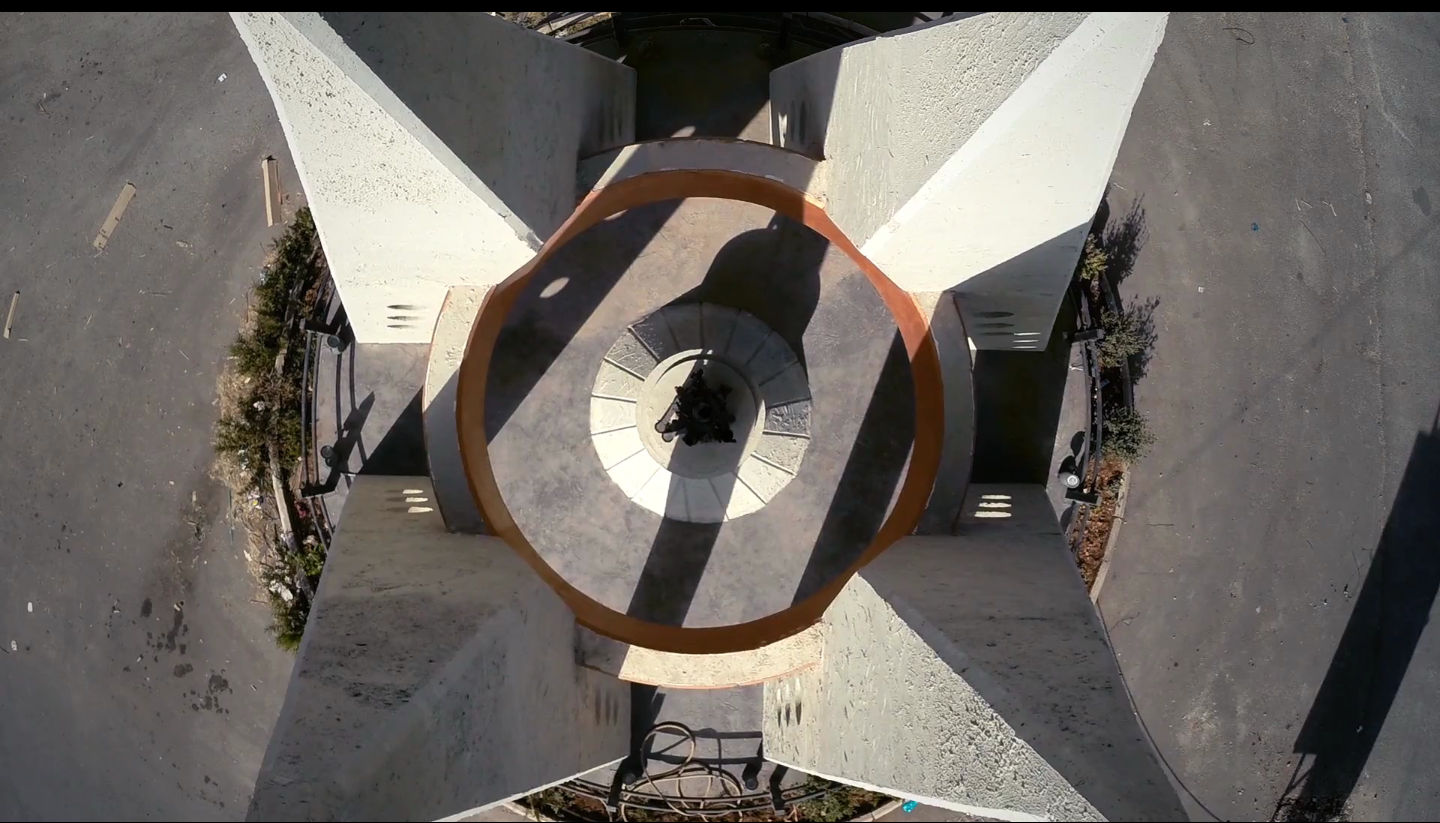

The Fourth Stage looks at the increasing number of monuments with an abstract vernacular in south of Lebanon, specifically in locations such as valleys and roadsides that bear no particular symbolic significance. The architects of the Ministry of Interior’s Information Office had plans for monuments and sizable works covering entire mountains. It would be impossible not to be moved by the intensity of these monuments. Upon venturing into the area, one immediately encounters a new visual identity that fully occupies the space. On the other hand, on a popular level, confectioners produce a somewhat different type of monument: sweet molds for religious holidays. These molds for all occasions represent an alternative form of architecture. This film attempts to trace the paths of ideology and mythology that are seeking to combine new narrative and visual forms and reshape the geopolitical landscape of South Lebanon.